Sharing ideas and inspiration for engagement, inclusion, and excellence in STEM

The garden at the Paris Gibson Education Center, an alternative high school in Great Falls, Montana, is much more than a spot where plants grow.

It’s a place where students can do their homework or simply relax. But the garden also plays an important role in celebrating Native culture—and it provides a jumping-off point for incorporating Native culture into all classes, including STEM.

For example, in addition to peppers, corn, and many other plants, students have grown sweetgrass, sage, and tobacco, which many Plains tribes consider sacred, said Jordann Lankford-Forster (Bright Trail Woman), the lead teacher for Paris Gibson’s interTRIBAL Immersion program.

“We use all of those items to smudge with,” she said. “We’re intentional to incorporate the aspect of reciprocity into the harvest of these sacred materials too.”

After sweetgrass is harvested, students are in charge of braiding it, an important practice among Plains tribes, Lankford-Forster said.

Photo source: Paris Gibson Education Center.

Upholding a State Mandate

For more than two decades, Montana has required Indian Education for All (IEFA) to be taught at all schools and in all subject areas across the state.

As an IEFA instructional coach for Great Falls Public Schools, Lankford-Forster helps other educators in the district incorporate Indigenous content into their classrooms and curricula—and she said growing gardens at more schools will be integral to this work.

“Even if it’s small, a garden can help us start teaching that cultural content and traditional uses of plants,” Lankford-Forster said. “A garden also helps give the students ownership over their education and put them in a space of responsibility.”

Incorporating Multiple Aspects of Native Culture

The garden at Paris Gibson is a crucial vehicle for learning about and celebrating Native culture in STEM, but students have many other opportunities to do so.

For instance, after they participated in a bison hunt several years ago, students in the interTRIBAL immersion program learned about multiplying fractions. Additionally, they practice archery in gym class every week and then discuss speed and velocity in science class.

Students can also earn math and science points by taking part in a beading project in which they use calculations to ensure symmetry—and younger students have the opportunity to bead graduating seniors’ mortarboards.

graduating seniors’ mortarboards.

Photo source: Paris Gibson Education Center.

In addition, students are learning about aquaponics in science class. Specifically, they are growing lettuce hydroponically and using waste from fish as fertilizer—and when the fish die, their remains are used as fertilizer in the outdoor garden.

“Native American people have been using fish as fertilizer for thousands of years, so the idea of putting fish into the ground is important, as well,” science teacher Jonathan Logan said. “We don’t want the fish to die, but when they do, it’s OK because we know what to do with them because we’ve learned from history.”

A STEM unit focused on food sovereignty is another way that Paris Gibson teachers have incorporated Native culture into the curriculum.

“American Indian people were self-sufficient and self-reliant until the ‘Removal’ and ‘Reservation’ Federal Policy periods, when they were no longer in charge of their food sources,” Lankford-Forster said. “So, we tell the story of those periods—not only what it meant for the depletion of land, but what it meant for self-sufficiency, as well as the diet and overall health of American Indian people.”

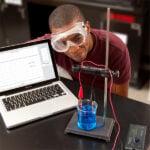

Logan supplements and quantifies this story through science experiments that demonstrate the nutritional value of simple carbohydrates compared with lean proteins.

“We set up a test tube, and then we burn the food and measure the actual kilocalories,” Logan said. “Students realize that when a Cheeto burns, it goes up fast, and then it’s gone, whereas if you’re burning a protein like beef jerky, there’s a lot more energy in there that lasts longer, and it’s better for your body. Now, all of a sudden, it’s not just someone telling them about it—they’re seeing it for themselves. It’s pretty awesome.”

The food sovereignty unit also incorporates physics. Specifically, students weigh themselves, run up stairs, and then start doing calculations.

“They measure each stair, so now they have a distance of each step. Well, then, how many steps? So, you’re multiplying to figure out the total height,” Logan said. “Then they time themselves running up the stairs, and we calculate how many calories it took. And then we ask, ‘How much jerky would you need to eat to get up there? How many marshmallows? OK, this mountain’s 1,000 feet. Now how many calories would it take? Would you rather eat marshmallows or beef jerky?’”

(Note: Vernier offers several experiments related to this topic, including “Investigating the Energy Content of Foods,” “Heart Rate and Calories,” and “Food is Fuel.”)

Photo source: Paris Gibson Education Center.

Looking at the Benefits and Examining Best Practices

Teachers at Paris Gibson are committed to ensuring that all students have the knowledge and skills they need to achieve postsecondary success. Celebrating Native culture and incorporating it into all classes, including STEM, is conducive to meeting this educational goal, Lankford-Forster said.

“It’s really important to demonstrate to not just our Native students, but to all students, the traditional mathematical and scientific knowledge that American Indian people had and still have today—our culture is alive and well,” she said. “Plus, if one of our goals is to get our kids college and career ready, we don’t want college to be the first time that they’re hearing this information.”

Lankford-Forster and Logan offer the following best practices for incorporating Native culture into STEM classes or an entire curriculum:

- Begin by picking one thing and doing it well. “For example, don’t start a garden with 10 kinds of sage and sweetgrass,” Logan said. “Just see if you can grow one kind of sweetgrass.”

- Highlight student voice. “Let the kids guide you; they are going to tell you where they want to go,” Logan said. “Just be sure to listen.”

- Pick a standard and flip the content. Lankford-Forster said the food sovereignty STEM unit is a great example of this approach. “You can substitute and trade so many of these discussions that you would normally be having because it’s part of your curriculum anyway and just infuse Native content that way,” she said.

Share this Article

Sign up for our newsletter

Stay in the loop! Beyond Measure delivers monthly updates on the latest news, ideas, and STEM resources from Vernier.